Most of the matter in the universe is completely invisible to us. It’s called dark matter because it does not absorb, reflect or emit any light. It makes up more than four times the amount of visible matter that we can detect. If we can’t see it, how do we know it’s there? Because of its effects on what we can be seen. Some argue that the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) disproved the idea that dark matter exists. It didn’t.

In the 1930s, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky found that there simply wasn’t enough visible mass to account for the gravitation needed to keep the Coma cluster together. He proposed the existence of “missing” or “dark” matter, but he was dismissed. 40 years later, Vera Rubin found that the stars at the Andromeda galaxy’s edge were orbiting the central mass just as fast as stars closer to the center. This was impossible according to Newton’s laws. This observation showed that there was more mass in galaxies than what we could actually see.

50 years later, today, we still don’t know what dark matter is, but we know it’s essential to the structure of the universe, and affected its evolution in the initial seconds after the big bang. We can see it by studying the tiny variations in temperature for the earliest detectable light of the universe – the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB). These fluctuations represent tiny fluctuations in the density of matter. We can calculate what this pattern would have been without the presence of dark matter. But that’s not the pattern that we see. We see a pattern where the dark matter must be at least 4-5x ordinary matter.

As a result of the effects of dark matter, small clumps of ordinary matter were beginning to form prior to the CMB, creating regions of higher and lower density in the universe. Those early clumps acted as gravitational seeds that resulted in clusters and superclusters of galaxies. Without dark matter, ordinary matter may not have formed galaxies and clusters at all.

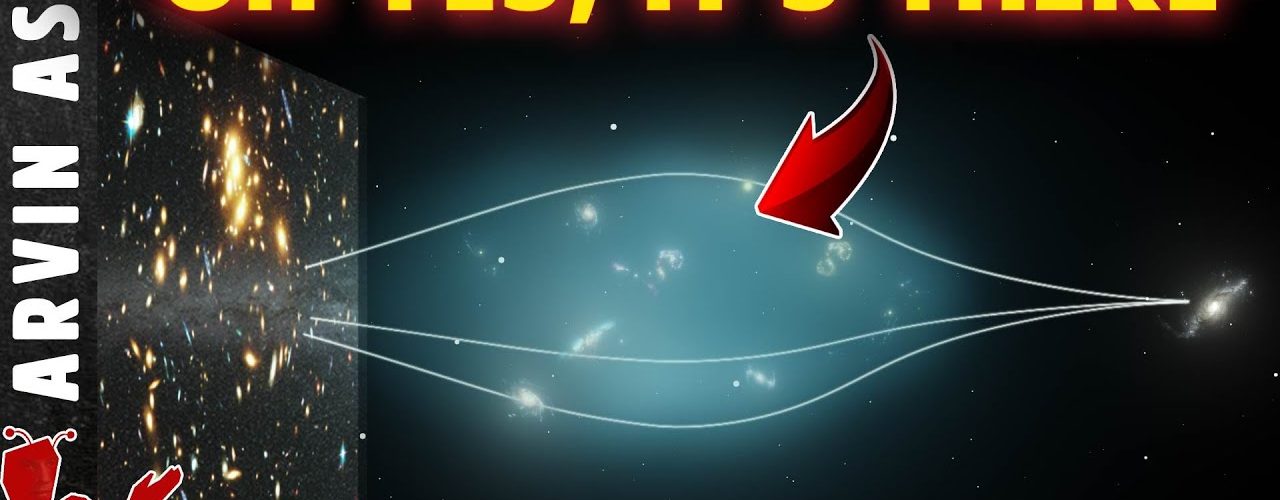

We also know that Dark Matter exists around individual galaxies because of gravitational lensing. This is where light from distant objects bends around massive clusters of matter due to their gravitational pull. When astronomers map these distortions, they find that the lensing effect cannot be accounted for by the visible matter within the galaxy. So most of the mass in galaxies based on their lensing effect is missing. It can then be deduced that a vast invisible dark matter halo must exist, which would account for the discrepancy that Vera Rubin found.

Some argue that MOND or Modified Newtonian Dynamics can account for the observations without the need for any Dark matter. It proposes that by manipulating Newton’s equations, we can show that the gravitational force is weaker at the edges of galaxies. But there’s not theoretical basis to make these changes other than to force fit the observational data. Also the recent JWST data does not rule out Dark matter, as some people have suggested. We should not jump to conclusions based on a few observations over a handful of years. Further research is needed to confirm the current findings. Our models may simply require some adjustments.

#darkmatter

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for dark matter comes from the Bullet Cluster, which is the aftermath of a collision of two galaxy clusters. The gravitational lensing data shows that dark matter pulled ahead of the visible matter, which is exactly what we would expect if dark matter existed. because dark matter only interacts through gravity, It does otherwise interact with ordinary matter, so it passes right through it.